This site focuses on the process of harvesting pen clams and creating textiles from their byssal threads. It is intended to be a guide for anyone interested in the tools and methods used to create textiles similar to those historically produced in Italy, called byssus or sea silk. For more information about the history of byssus and for a catalogue of samples found in collections throughout the world, visit the Natural History Museum of Basel, Switzerland’s Sea Silk Project website at www.muschelseide.ch/en.

I do not encourage live harvesting. Too many people harvesting too many clams would certainly damage our coastal ecosystems. I advocate for using the byproducts of clams that are specifically grown and/or harvested for food, to reduce waste and make use of the whole animal. Only gather byssus from live clams as allowable by local and national law, ensure that the species of clam you are gathering is not endangered or threatened, ensure that the environmental conditions where you are gathering are supportive of overall species health, and, as always, gather respectfully.

What is Byssus?

Many different species of bivalve mollusk produce protein filaments called byssal threads that they use to move or anchor themselves. A collection of these threads is often referred to as the beard, and sometimes as byssus. Textiles made from these threads are commonly called byssus or sea silk. The Italians call it “il bisso”, so I will refer to this fiber as byssus.

References to byssus textiles exist in historical records across Mediterranean Europe, the Middle East, and China and date back nearly 2,000 years. Traditionally, byssus is harvested from the Pinna nobilis, or Noble Pen Shell clam, which is native to the Mediterranean and can grow to be over a meter tall. The animal’s six-centimeter-long filaments are gathered and spun into a naturally golden thread that has been valued as nearly mythical for centuries.

Today, overfishing and pollution have endangered Pinna nobilis colonies. It is now illegal to harvest these animals. Italian artisans working with byssus today use old stock left over from a defunct local industry, use the byssal threads of other species, or they collect the byssus humanely.

The Quest

In 2017, I found myself sitting on a plane, alone, and headed for Italy. A few years earlier, I’d read a BBC article about a mysterious woman named Chiara Vigo who lived on an island off the coast of Sardinia. She spent her life diving into the sea and harvesting golden fibers from Pinna nobilis clams that she spun and wove into elaborate tapestries but would not sell. I was hooked. My interest in byssus went beyond mere fascination: I had to meet this woman and know this fiber, and so I did.

I have spent most of the last decade learning what I can about the process of this craft, while also seeking new sources of material that will allow it to continue. I have been honored to meet with and learn from various Sardinian artists still working with byssus today (and there are several, despite the popular narrative), clam farmers and scientists studying coastal ecologies for food production, and scholars who have created a life’s work from the study of pen clams and byssus.

My own studies have taken me to the coast of North Carolina where I have harvested samples of Atrina rigida fiber for experimentation, under the supervision of a coastal ecologist. From these experiments, coupled with what I’ve learned from Sardinian artists, I’ve created a guide to collecting, desalinating, cleaning, and spinning byssus for fiber craft. Given the lack of detail for this process in the historical record that I’ve had access to, I cannot be certain that this guide is historically accurate; however, I am certain that this process works and does result in beautiful thread.

Future project goals include identifying persons or industries who are harvesting pen clams for food and encouraging them to make the byssus available to artisans.

Many Thanks

My research would not have been possible without the following individuals and organizations:

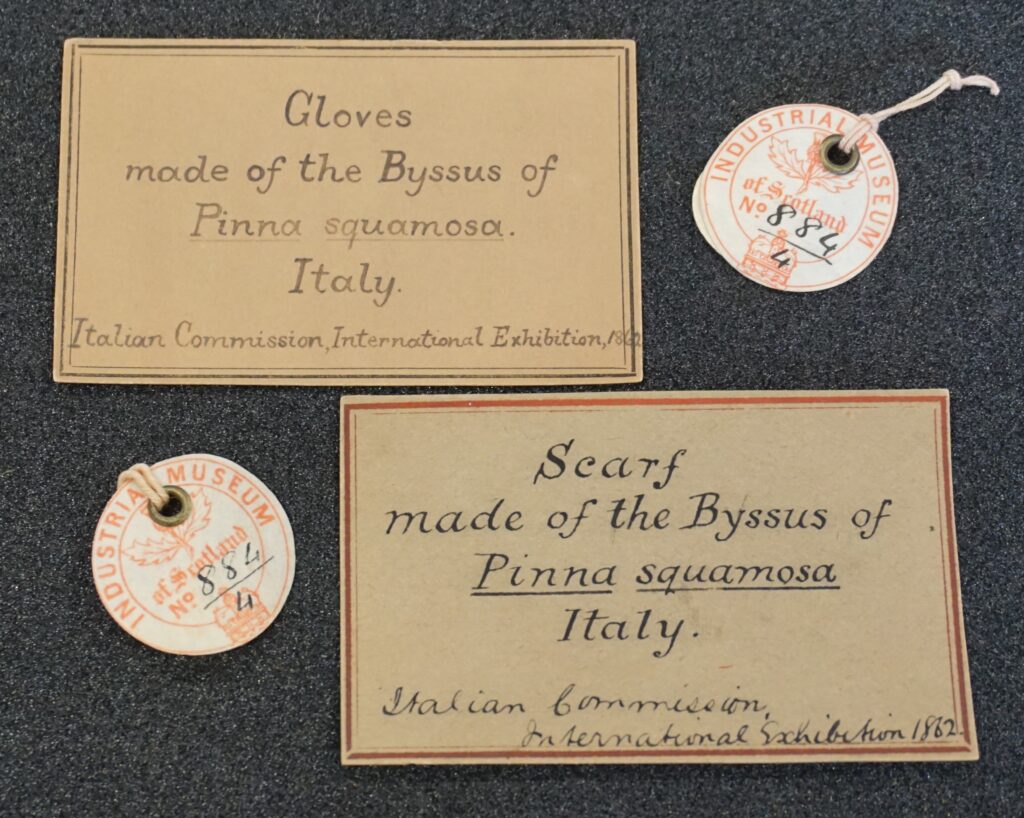

Many thanks to the curators and institutions that have hosted me as I researched historical examples of byssus held within their collections, including: The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History; The Smithsonian National Museum of American History; Musée océanographique de Monaco; Musée des Confluences – Lyon; Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle – Paris; Musée d’art et d’histoire Paul Eluard – Ville de Saint-Denis; The Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford; and The National Museum of Scotland.

Thanks to Dr. Felicitas Maeder of the Natural History Museum Basel, Switzerland, for sharing her research, advising mine, and connecting me with Sardinian artisans, including the sisters Assuntina e Giuseppina Pes and the artist Arianna Pintus. Additional thanks to Arianna Pintus for hosting a workshop for me at her studio in Sardinia, and to Chiara Vigo for providing me with a sample that I modeled my own thread after.

Thanks to Dr. Estevão Rosim Fachini and the University of Puerto Rico at Rio Piedras for your analysis of the fibers of various clam species.

Thanks to Julius Morris and Dr. Chuck Weirich for helping me to find clams and understand the environmental challenges that they face.

Thanks to Joyce Matthys, who I had the pleasure of meeting in 2019. She spent years harvesting and spinning byssus from three pen shell species that had washed to shore in Florida after storms, and she remains the first and only other person that I know of to work with American sea silk. She kindly shared her process with me in 2018, and she also exhibited her findings at the Sanibel Shell Show in 2016.

Thanks to Dr. Benjamin Weinberg, for thinking this was cool, diving real good, and encouraging all of it. And thanks to Elizabeth Neason for running unusual French errands.

This research was supported by a Craft Research Fund Artist Fellowship from the Center for Craft.