For this research, I analyzed 26 artifacts held at 8 institutions located in the United States and Western Europe, including: The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History; The Smithsonian National Museum of American History; Musée océanographique de Monaco; Musée des Confluences – Lyon; Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle – Paris; Musée d’art et d’histoire Paul Eluard – Ville de Saint-Denis; The Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford; and The National Museum of Scotland. One sample was later discovered to be degraded silk and was excluded from analysis.

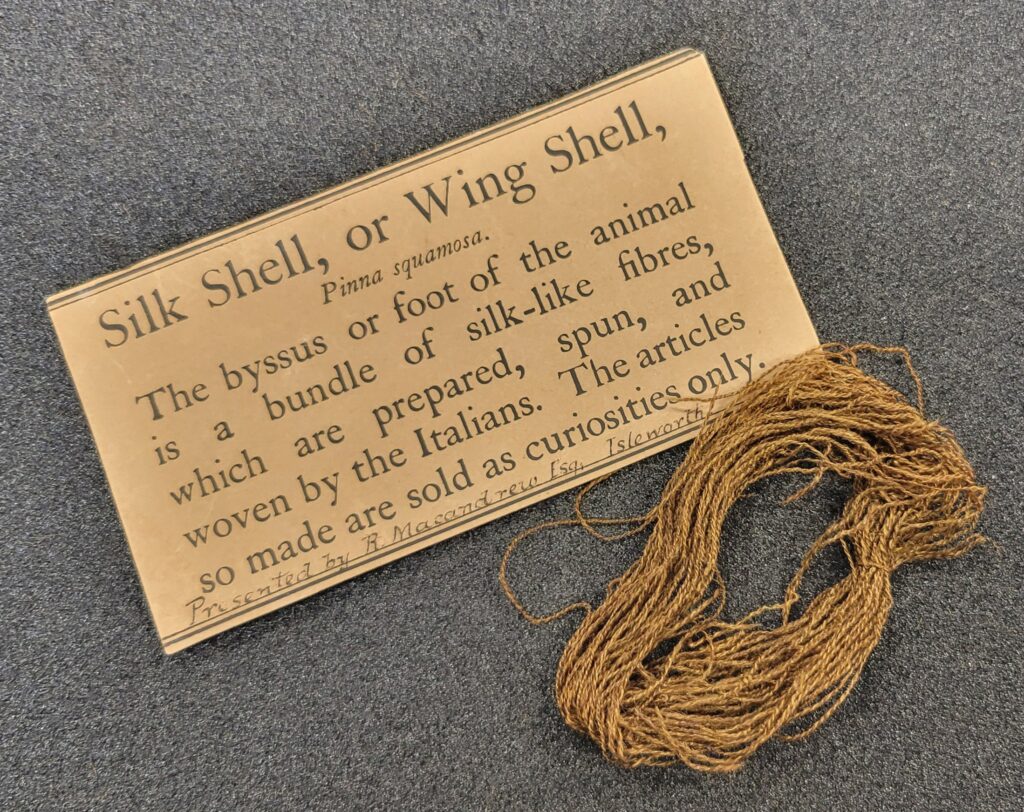

Artifacts included unspun and unprocessed byssal threads from Pinna nobilis, to inform average diameter of fibers; spun thread; and finished textiles. This sample included textiles that ranged in age from the 14th century to the mid-20th century. All finished textiles with known origin were produced in Italy – either in Sardinia or Taranto (the southern coast). The most recent sample, a length of yarn spun from the noil waste product of the combing process, is located at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and is noted to have been produced in Biella, Italy (north of Turin near the Swiss border), in 1965. The oldest samples, which are also the oldest known byssus artifacts in the world, are fragments of knitted caps from the 14th century and are located at the Musée d’art et d’histoire Paul Eluard – Ville de Saint-Denis.

For each artifact, I noted age and location of origin, if known, and I evaluated each sample based on size, weight, color, construction technique, construction characteristics, yarn characteristics, observable fiber qualities, and microscopic assessment of fiber diameter. My intention was to analyze historical byssus fabric samples in order to inform a guide for modern day production.

Fiber and Thread

All of the 25 byssus artifacts analyzed from these 8 collections are presumed to contain the byssal fibers of Pinna nobilis. Many of the samples explicitly noted that they were made of Pinna nobilis, including all of the textiles and thread samples produced after the late 19th century. There is no reason to believe that earlier textiles were made of a species other than Pinna nobilis, but there is also no way of knowing without genetic analysis.

Loose fibers were available for microscopic analysis from 16 samples that showed a wide range of fiber diameter from 25 to 50 microns, with an average diameter of 37.5 microns and a median diameter of 40 microns.

Eleven of the objects were finished textiles made from spun thread. All of these objects were made from 2-ply yarn. The oldest samples, those originating in the 14th century, were made from thicker yarn with less twist. The finest yarns with tighter twist are thought to have been produced in the mid- to late-19th century. Some of these samples showed evidence of pigtailing – when a thread is spun too tightly to be balanced and twists back upon itself during the plying process, creating small protrusions. The grist of these yarns – the ratio of length to weight – or the diameter in wraps per inch is difficult to determine in finished textiles. The analysis of the finest sample is estimated to have approximately 10 to 15 individual fibers per ply.

Fabric

Of the 11 finished textiles, 10 were knitted objects and one was knotted in a net-like fashion. Six were knitted gloves (two objects were a complete pair and four were single gloves) dating to the 19th and 20th centuries, two were knitted caps dating to the 14th century, one was a large square knitted shawl dating to the 18th century, one was a knitted belt dating to the 19th century, and one was a 19th century knotted net-like scarf.

Of the 10 knitted objects, all were plainly knitted in stockinette stitch save for the glove held in the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. This particular artifact is fascinating both for its intricate design and also for its place in the Smithsonian’s collections. The glove is not of American origin, and it is noted to have come from Japan in a batch donation of Japanese objects from the US Fish Commission prior to 1956. It is believed that the glove was brought to Japan from Italy sometime in the late 19th or early 20th century, though this requires further investigation.

The oldest knitted objects were knitted with the largest gauge. The 14th century caps at 2.75 and 3.5 stitches per centimeter (6.7 and 8.6 stitches per inch). The finest of the objects was a complete pair of gloves from the collection at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle – Paris. These gloves were impossibly delicate and were knitted at a gauge of 11 stitches per centimeter, which is an astonishing 27 stitches per inch. Most other samples fell closer to the 7 stitches per centimeter (17 stitches per inch) range.

Six of the artifacts were finished items made from unspun byssus fibers and made to resemble fur. All of these objects are located at the Musée océanographique de Monaco and were produced in 1910 in Caroforte, Sardinia. Of these items, four were tassels used to adorn curtains, fans, or similar; one was a purse made with brushed, unspun byssal tufts; and one was a “faux fur” hat made with byssus using mechanical means. This was the only clear evidence of mechanical production in any of the examined textiles.

Many of the objects are too delicate to be touched. However, in the circumstances where this was allowable, the object were very soft. They felt slightly silky but were more reminiscent of fine wool. Many of the objects, however, have begun to degrade significantly. These objects are brittle, and the fibers flake excessively. Because of the rarity of these objects, conservation methods may be unclear or difficult.

In modern times in Sardinia, because Pinna nobilis is a protected species and byssus is difficult or illegal to obtain, many artisans working with old stock from the defunct textile industry, humanely harvested fiber, or different species weave byssus into a background of handspun linen to create tapestries. This both highlights the fiber and limits the amount necessary to produce a work.

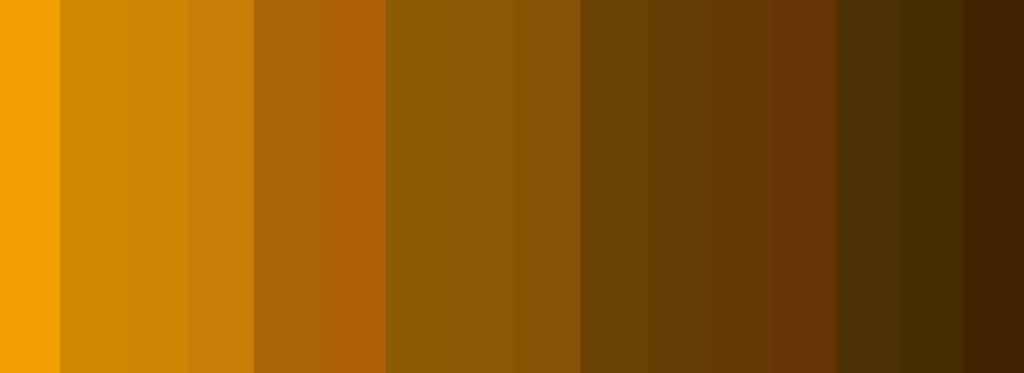

Color

The color of the byssus fiber used in each artifact varied widely according to the chart below. All of the samples have a metallic, coppery tone: